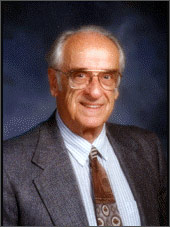

It wasn’t until years after he was gone that I finally understood my grandfather, Papaw. Ottie to his friends, Dr. Apel to his patients. And savior to countless soldiers from everywhere in the Korean War.

As a kid, I knew Papaw was quiet, until you got him talking about his horses. He loved his Tennessee Walking Horses, and later on, his Thoroughbreds, and if you got him started on bloodlines and whatnot, he’d talk all night.

In the time I knew him, he loved to help people, and he loved his family. He loved his wife, Joan (pronounced JoAnne), who wasn’t our blood grandmother but might as well have been (don’t hear that wrong: he loved his first wife too, my dad’s mom, Marjorie. She died of cancer when Dad was a child). And he loved his three-legged cocker spaniel, Ginger, or “Gingie” as we liked to call her.

I remember all of us cousins trying so hard to get him to pay attention to us. I remember some family members were always a little discontent that he didn’t do more as a grandfather, like going to games or calling to chat or sending birthday cards or whatever. It may not have been just like that, but it seemed that way when I would listen to the grownups talk when I was supposed to be in bed.

I didn’t know he was a hero until years later, and it’s honestly because he didn’t talk about it. If you know a combat veteran, you know that most of them don’t want to share their experiences. Bits and pieces will come out: “Those politicians can act like that because they’ve never seen a man’s face blown off in front of them,” and such statements, but rarely do you hear the stories, because they’re too personal. They hurt too much, and they’ve been buried too deep.

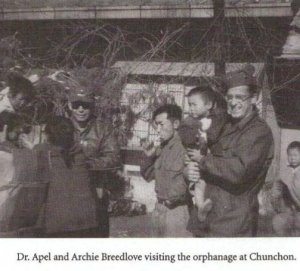

One time when I was old enough to kind of understand there was a war one time, I remember Papaw taking out some slides of Korea. The pictures didn’t look too much like a war to me. It was a lot of smiling men and women, and I remember seeing some kids in there. And of course they were all black and white. Why couldn’t we just talk about horses some more?

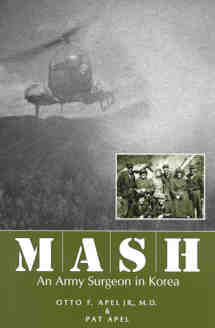

Years passed. When I left for Ole Miss, Mom and Dad moved to Ohio, where Dad began working on a book with Papaw. They decided to call it “M*A*S*H: An Army Surgeon In Korea.”

Years passed. When I left for Ole Miss, Mom and Dad moved to Ohio, where Dad began working on a book with Papaw. They decided to call it “M*A*S*H: An Army Surgeon In Korea.”

Dad talked about it some, but I was a freshman or sophomore in college. I had no time for war books (or really any books. Who reads in college?), unless I could pretend I read them to impress some ROTC guy.

Then I proofread bits and pieces of it at some point, and I thought, “I’ll probably read this one day. It’s kind of cool they made the show from stories like this.”

I found out Papaw had been a consultant to the actual show. Some of those episodes were actually based on his recollections. Then “History Vs. Hollywood” came out and did a segment with him. Dad was so proud. I thought, “Cool, maybe I’ll see him on TV one day.”

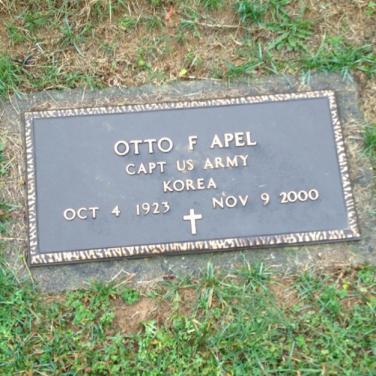

I was on a company retreat with the PR firm I was working for just out of college when one of the partners, incidentally an old friend of my father’s, pulled me aside and told me Papaw had died. When I called home, it turned out he had a heart attack on the stage as he was being inducted into the Ohio Veterans Hall of Fame. It was an ending fit for a hero, and the whole family, except me, was there. I still wish I had been there.

I’ll never forget his funeral, and the flag on the casket and the 21-gun salute. But what stuck out most to me was my brother, who was about to turn 13, as he walked up to the casket. He put his hand on Papaw’s casket, and I saw a tear run down his face.

I’ll never forget his funeral, and the flag on the casket and the 21-gun salute. But what stuck out most to me was my brother, who was about to turn 13, as he walked up to the casket. He put his hand on Papaw’s casket, and I saw a tear run down his face.

I’ll also never forget my dad giving a eulogy about Papaw, and he cried a little when he looked at Joan and reassured her, “You were the love of his life.”

I’ve only seen my dad cry maybe three times, and I still really didn’t take in the scope of what Papaw’s life had meant.

A few months after his death, I turned on the TV and saw Papaw’s face on the History Channel one night and listened to the things he talked about. It was pretty surreal, and I kept thinking, “Why didn’t he ever tell us this when we would all sit around and talk? Or did he? Did I listen?”

Then I became a volunteer firefighter and first responder.

That sentence in itself, as I have alluded to a million times, stands alone in my life. Something changes you at a very basic level when you have had someone die in your arms. For me it was a third-grader named Davonte McNulty, who was hit by a car on Oct. 7, 2008. I did the breathing on the CPR as Steve Davis, a firefighter who was a dear friend that I had the utmost respect for, did the compressions and John Riggs, a paramedic who taught me a lot of what I know, was hooking him up to the machines and whatnot. Steve has since died in a plane crash, which makes the memory even more poignant. That was a tough story to write, and I drew a lot of criticim for it.

But I knew that I gave that child the last breaths he had on earth. It wasn’t “something” that had changed. It was everything in me that changed that day. It wasn’t just seeing a body after a wreck. It wasn’t finding a body in the ashes. It was watching a life leave earth as I fought furiously and hopelessly to save it. That’s where I started to “get it.”

Not long after that, I was driving down the road and I got a picture in my head (like a vivid memory, almost a flashback, and to this day I don’t know where it came from) of looking down at my hands, only they weren’t my hands, in white latex gloves, covered in blood in a badly lit room. Suddenly I knew those weren’t my hands, they were Papaw’s, and I knew where this blessing and curse of wanting to help people and save people came from.

After that, I went back and read Papaw’s book. I was struck by the part where all the other med school students were talking about how to get out of going to serve as Army doctors at a softball game, and Papaw told them he’d decided he figured he’d better go.

After that, I went back and read Papaw’s book. I was struck by the part where all the other med school students were talking about how to get out of going to serve as Army doctors at a softball game, and Papaw told them he’d decided he figured he’d better go.

When he got there, he worked for days (I believe it was 48 hours straight, but for some reason I’m trying to tell you 72, probably because I think he’s a superhero and could totally do it) without stopping or sitting down, and when it was time for a break, they had to cut his boots off him because his feet and legs had swollen so much from standing.

The scene that sticks out the most, though, was a radio call where it was clear a unit was in combat and it was bad, and they were going to need medics. Papaw and one of the helicopter pilots had flown out there and found one lone American soldier, sitting in a ball among the bodies of his fallen brothers, the lone survivor.

Papaw and one of his colleagues disobeyed direct orders on a forbidden medical procedure standard that they knew was working when they did it their way. They faced a serious chance of court martial, but a few of the wiser higher-ups pretty much pretended they didn’t see what they had seen until the procedure was approved.

The men he dealt with were just babies, for the most part. Nineteen and 20 years old, and they were torn limb from limb. In retrospect, though, they weren’t that much younger than him, just out of medical school. He does also talk about an older man, an officer, who came in to get patched up and left prematurely because his unit was going back into battle and he wasn’t going to let them go alone. Papaw said he assumed he didn’t make it through that battle because he never came back. That officer’s face haunted him for a long time.

Stories like these gave me a new view of my grandfather. No wonder he was quiet. No wonder he wasn’t into small talk. No wonder he lost a lot of money when he went into private practice because he would trade medical services for baskets of eggs, or a bag of apples. He loved people, and he wanted to do whatever it would take to save them.

No wonder he loved those horses. They were beautiful. They were light years away from the death and despair he’d seen and held in his own bloody hands for hours and days at a time.

And no wonder when people seemed to be more interested in bickering about petty things like who was on the school board or who’s kid was the better ballplayer, he wasn’t involved. He was reading or looking out the window, or he would go out to the barn and he would look at and talk to the horses.

Even though Memorial Day has officially passed, I think of Papaw: I think of the men he couldn’t save, and the fact that he lived with their faces for the rest of his life. I picture the look on his face as he made the choice to boldly disobey orders to save lives.

And I know that I got my love for horses and dogs, my need to run into the fray to help, and my Dad, who is the greatest man alive, from Papaw. When there are faces and pictures from wrecks and fires and medical calls I’ve worked and stories I’ve covered that haunt me, I think of Papaw and the man it made him.

Let us never forget those who made the ultimate sacrifice, in whatever way they did. A lot of people who come home from the battlefield come home broken, and a lot come home with broken hearts.

As those who have served would and have said, “Hooah, Captain Apel! We’ve got it from here.”

And as I would say, and do: Thank you, Papaw.

This blog was originally posted in my Clarion-Ledger blog, “Boots and Badges.” It has since been deactivated.

One response to ““Hooah, Capt. Apel! We’ve got it from here.” The story of Papaw, the MASH doctor”